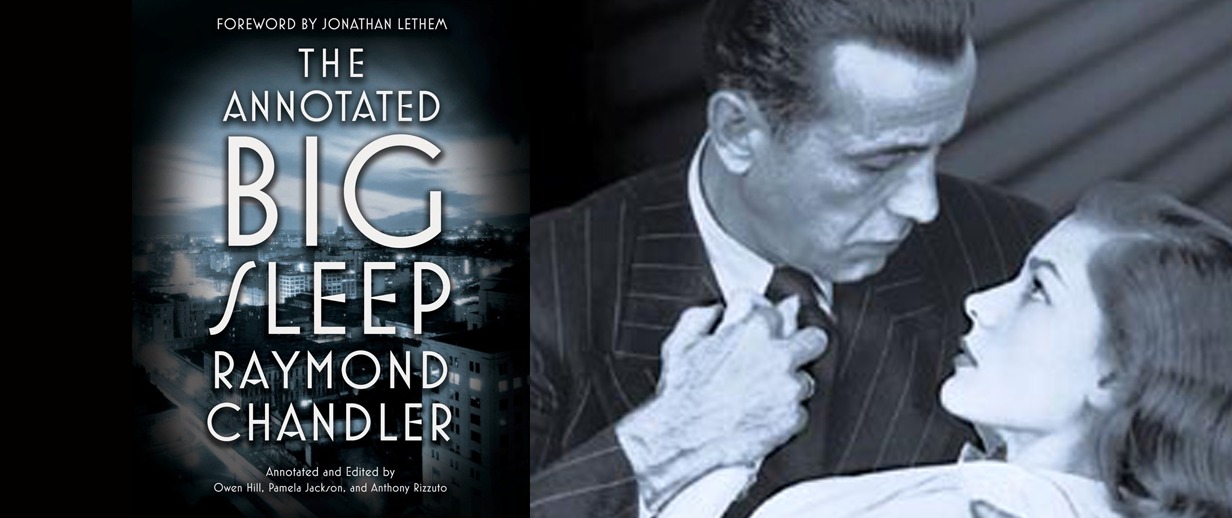

Annotated and edited by Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto with a forward by Jonathan Lethem

I’m giving this book 5 Stars.

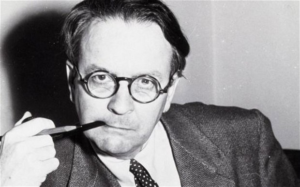

The Heart and Soul of Raymond Chandler’s fiction

If I were ever to teach a course on creative fiction writing, I’d assign The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler, his first novel published in 1939, and then The Annotated Big Sleep published in 2018. The Annotated Big Sleep eloquently and interestingly takes its readers into the thoughts of the brilliant Raymond Chandler with poignant comments by Chandler and his novels and his responses to his critics and social commenters of his time. The Annotated Big Sleep elegantly and thoroughly addresses the question: What is literary fiction? How does it differ from nonliterary genre fiction (which most noir genre detective fiction is)?

My discussion takes the liberty of commenting at times on, by way of comparison, two recently published collections of stories each by an Irish author who is regarded (though not by me) as a master of literary fiction. I refer to Last Stories by William Trevor (1928-2016) published in 2018 and The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) published in 2019.

Literary fiction reveals its time but remains meaningful for future generations. E.g. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. A Tale of Two Cities

Literary fiction has style, which Chandler deemed imperative. Literary fiction prose has prosody (sound and rhythm) and is resplendent with metaphors that illuminate as Aristotle argued in The Poetics. I loved Chandler’s critique of Ross MacDonald’s simile: The rust on Archer’s car was like acne.

One must have talent to write good metaphors. Chandler’s are brilliant. In TBS Chandler uses the convention of pathetic fallacy seamlessly. Chandler’s references to canonized literature is also nicely done. Think Remembrances of Things Past.

According to the annotated version, Chandler believed that literary style must be elevated over plot. Personally, I don’t see plot and style at war. And I disdain the modern thinking that plot is irrelevant and that the essence of fiction is only the characters. Think William Trevor and other long and boring New Yorker stories. Though some are quite good. Think T.C. Boyle or Alice Munro.

And of course, Chandler’s dialog sparkles. You won’t find exposition in his dialog, meaning he won’t use dialog to tell the reader something that the other character knows. There is subtext in Chandler’s dialog, i.e. the character usually means something other than what she or he says or what she or he says has more than one meaning.

Can any of us remember a quote from a William Trevor or an Elizabeth Bowen story? Months or years later, do we care about what happened to their characters? Or even remember? Chandler’s stories are chockfull of memorable quotes. Think “Dead men are heavier than broken hearts.”

Literary fiction advances or illuminates a moral POV. Think The Divine Comedy.

Nonliterary genre fiction is formulaic no matter who the characters might be. Typical best-selling romance formula: Girl with noticeably large breasts and long silky (usually blonde) hair notices boy with fabulous physique on page 2. Girl kisses boy on page 5. Boy has the opportunity to remove girl’s bikini top on page 10 but refrains from doing so because he respects her. Boy meets girl’s parents and they hate him, order girl not to see him again. And so forth.

Nonliterary genre lacks subtlety.

Marlowe’s character is consistent but he actions aren’t. Chandler’s books thrive on subtext and pretext.

In 2003 in a speech at the annual National Book Award ceremony (I highly recommend it) Stephen King argues, and I agree, that a hallmark of literature is that it illuminates its time. TBS is famous for illuminating the look and feel of Los Angeles in 1939. Sternwood, we learn in the Annotated Version, was likely a surrogate for the L.A. oil baron George Hancock of Hancock Park fame. One had to be wealthy to hire a private sleuth and so Chandler’s characters are the aristocrats and/or the nouveau riche and the grifters who feed upon them. Chandler left the unemployed to Upton Sinclair. As Scott Fitzgerald said: I write about the rich because those are the people I know.

When I was researching Ursula Le Guin in preparation for writing my review of The Dispossessed in case you missed it), I was surprised to learn that Le Guin chose the Sci-Fi genre because it paid well. I suspect that Chandler chose the detective genre because he admired the writing of Dashiell Hammett (perhaps Poe and Conan Doyle as well) and because he liked it.

In How Fiction Works its author James Wood (literary critic for The New Yorker) explains that it is not only attention to details and objects that an author includes in a scene that is important but which details and objects the author chooses. Bad writers choose boring, irrelevant details. The objects in TBS have life and often multiple meanings. Wood uses Madam Bovary to illustrate his examples. Flaubert was exquisite when it came to describing physical details. IMHO so is Chandler. Think of the stained glass above the entry door to the Sternwood mansion.

William Trevor wasn’t terrible when it came to making his scenes vivid. His characters were simply boring because of their passivity and his stories were boring because of their deus ex machinus or lame epiphany endings. Elizabeth Bowen began her stories with vivid descriptions of the landscape but this was boring because the descriptions weren’t integrated into the stories. Those descriptions delayed the introduction to the characters and after all, we read fiction to meet the characters, not the trees.

Chandler’s books, like Arthur Conan Doyle’s, like Charles Dickens’s, have given us cultural icons, and life lessons. Trevor’s stories end with lessons, epiphanies, but they are lessons meaningful to the characters but lost on posterity. Will a William Trevor story ever be made into a motion picture? TBS has been made into how many?

Dickens novels were first published in chapters in pulp-paper magazines. But Dickens novels, resplendent with details, descriptions are about characters that generations of readers have cared about. His long descriptive wonderful iconic opening to A Tale of Two Cities is about the people of London and of Paris in 1780.

Misogyny. I erred last night when I said Marlowe only hit Carmen on one occasion. Not that doing so was okay. Marlowe hits her again when they meet the next day at Geiger’s. Even says she seems to like it. Like the trench coat (not in the book) it’s stereotype, awful stereotype. I don’t think he’d write that today. He does have strong women characters.