I give it 5 Stars!

Life imitating Art imitating Life

In the Poetics, circa 335 BCE, Aristotle famously promulgated his rules of art, each of which rests upon this foundation: art mimics life. 2,224 years later, in 1889, Oscar Wilde published “The Decay of Lying,” the principal essay (a Socratic dialog actually, as irony would have it) in his collection Intentions. In “Decay,” one of the characters, a boy named Vivian, launches a poignant assault on realistic fiction in general and on the novels of Henry James in particular. There is, Vivian says, an abundance of boredom in fiction that imitates life and little art, if any, in imitation.

The polar positions in this chicken-or-egg debate can be reduced to absurdity, banality, or irrelevance, but Aristotle and Wilde advanced them earnestly as fundamental and critically important. Aristotle used his rule adeptly to illustrate the necessity of imitating human behavior in tragedy and comedy to promote verisimilitude. Oscar Wilde professed that art enriches the human spirit when it springs from imagination but not when it rests on imitation.

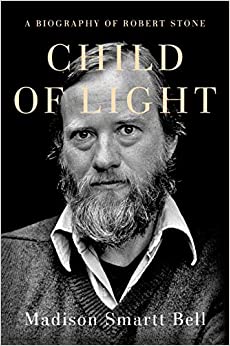

Robert Stone (1937-2015) was said by leading literary critics of our time to be one of our most important novelists. Child of Light is Madison Smartt Bell’s recently published, thought provoking, beautifully told authorized biography of Stone. It is a tapestry of an artist’s life from which his art cannot be unwoven without unraveling the whole. Child delves so deeply, meaningfully, and artfully into Stone’s work and his life that it casts light on the art of writing literary fiction and an understanding of where to look for the act of artistic creation along the Aristotle-Wilde aesthetic divide.

Robert Stone (1937-2015) was said by leading literary critics of our time to be one of our most important novelists. Child of Light is Madison Smartt Bell’s recently published, thought provoking, beautifully told authorized biography of Stone. It is a tapestry of an artist’s life from which his art cannot be unwoven without unraveling the whole. Child delves so deeply, meaningfully, and artfully into Stone’s work and his life that it casts light on the art of writing literary fiction and an understanding of where to look for the act of artistic creation along the Aristotle-Wilde aesthetic divide.

In Child, we learn that among his many accomplishments, Bob Stone published eight novels and made promising progress on another, one that he ultimately abandoned: Arctutus. All but one of his novels were critically acclaimed: He won a National Book Award, a Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and a Pen-Faulkner award. He taught creative writing to graduate and undergraduate students at U Mass Amherst, Johns Hopkins (where he had tenure), Yale, and other distinguished universities.

Bob Stone’s teaching career was especially impressive considering his limited formal education. By the time he was in high school “Bob had already acquired a good deal of knowledge about Western art history on his own, while lurking about New York museums as a smaller child. . ..” In his senior year at St. Ann’s (Catholic) high school, he had the highest score on the New York Regent’s exam, making him eligible for a four-year scholarship to NYU. He authored a story that was published, and he won writing awards. The New Yorker rejected a submission but asked to see more of his work. Notwithstanding these accomplishments, he was expelled from St. Ann’s for espousing “atheistic secular humanism.” “‘I felt like Martin Luther,’ he said, ‘. . . like a superhero.’” But without a high school diploma and hence decent job prospects, at 17 he joined the navy, where he ultimately earned a GED.

The derailment of Bob Stone’s formal education did not deter his pursuit of a self-education. In an article titled “Antarctica, 1958” published in the June 12, 2006 issue of The New Yorker, writing about one of his experiences in the navy when he was twenty, Bob Stone said: “When I went below to crash . . . I lay down to read with my pocket flashlight. I had “Ulysses” checked out of the Norfolk, Virginia, public library, and plenty of time to be patient with it. When we started sliding to port, I’d stay with Leopold Bloom for as long as I could tough it out . . .” In Child, we also learn of Bob Stone’s love and use of canonical poetry in his fiction, of his acting in and knowledge of William Shakespeare’s plays. Like Michael Faraday, like Abraham Lincoln, Robert Stone was an autodidact of the highest order.

Bob Stone was also an actor, a memoirist, a screenwriter. He was a reporter, the author of short fiction published in magazines such as The New Yorker. He received commissions from leading periodicals to write nonfiction articles and essays, including his memories of the 1960s and his travels to exotic locales. In short, as an author and a teacher, his was an amazing life of significant accomplishments and literary contributions. But he also suffered from, putting it mildly, a challenging childhood, depression, alcoholism, drug addiction, and chronic pain inflicted by gout and other lifelong ailments.

Child achieves its strengths by:

- Quoting Bob and Janice Stone, drawing quotes from a wealth of other authorities, and then interweaving these quotations with narrations, reflections, and commentary so that quotes and accompanying passages flow together as if originating from the same source;

- Telling the story of Bob Stone’s life and the writing of his novels in the distinct voices initially heard within the quotations;

- Structuring Child with sections that correlate with periods of Bob Stone’s life during which each of his novels was written; and

- Analyzing each novel by comparing episodes in Bob Stone’s life and one or more of his pertinent personality traits to the experiences and personality traits of his principal characters, presenting the reader with a unity of the artist and his art.

- Referencing an entry in one of Janice Stone’s journals about her first visit to Bob’s living quarters, M. Bell writes: “Bob’s room ‘seemed to be about knee-deep with discarded newspapers and socks. And I thought, this guy could really use some organizing. And then I thought—me, I can do that.’ As it turned out, she would be organizing Bob Stone for the next five decades.”

This is but one of many instances in Child where a quotation and the adjoining narration flow unimpededly from one to the other. This is done with such finesse that, as if by legerdemain, the biographer vanishes from the text, leaving the reader on her own with Bob or Janice Stone, with their thoughts and feelings, or with their friends, companions, or colleagues.

Quoting from an essay written by Stone for a book on Catholicism, Child begins:

I was born in Brooklyn on President Street . . .”

The omission of an opening quotation mark is a clever use of punctuation license. Farther down the first page, quoting from another source, the story continues with this intimate quote: “My mother didn’t have an honest bone in her body, God Bless her. . .. But she did care about me.”

In addition to the usual materials from which biographies are often constructed, such as interviews and book reviews, M. Bell had access to the Holy Grail—a metaphor he used in a short essay published in the May 21, 2020 edition of Air Mail titled “Child’s Play”—interviews with Bob Stone and accompanying commentary with “a psychoanalytic tack” taken and annotated in the late ’70s by Anne Greif for her dissertation in psychology.

Of her interviews with Bob, Greif wrote: “At times, his recollection was indeed so vivid that he seemed to be reliving in part the earlier time, and anger, anxiety, affection, love, and fright could be felt in the room.” And of Greif’s interviews of Bob and her commentary, M. Bell wrote: “This revelation had a double layer. Not only did I get the childhood in Stone’s own telling, but I also got to watch him tell it as a man in his prime—that version of my lost friend, and most admired writer, I had never before seen with my own eyes.”

How did M. Bell infuse rich veins of first-person quotations throughout Child to foster, intermittently, the feel of an autobiography, or to otherwise forge the close bond between a reader and a book’s principal character usually reserved for first-person narrations? Between the title of the Air Mail essay and the byline, this sentence appears: “Robert Stone’s biographer pieced together the novelist’s life by delving into his early years.” “Pieced together” does injustice to the literary accomplishment of Child of Light.

In the acknowledgments in Child, M. Bell says of his editor Gerry Howard: the latter would cut, and the author would suture. “Suture” is better than “piece together” but still fails to capture the experience of fluency engendered when reading a biography that slips effortlessly into and out of the first person, transitions between events and literary analyses so as to unite Robert Stone’s life and his art.

While the quotations intertwined with narration in Child vividly illuminate the nexus of Robert Stone’s life and his fiction, it achieves more. The quotations came from a variety of sources as they would in most well-written-and-researched biographies. As one would expect, tonal variations can be heard in quotations from different sources. But hearing the various tones emanating from the quotes echo in the narration connecting the quotes or in closely following passages is unexpected as this requires skill beyond the ability of most writers.

For instance, in the opening passages and later the reader hears matter-of-fact reportage: “I was born in Brooklyn.” The modulation of voice becomes most apparent late in the book with the appearance of M. Bell in person or as a character as it were. We hear in these passages his unique chronicling-Haiti-and-Hattian-lore voice, an English-speaking voice that occasionally speaks words and phrases in Haitian French and Kreyol. The voice of this narrator will be recognized by readers of M. Bell’s trilogy of novels set in Haiti that commence with All Souls Rising. These novels tell of the revolts that emancipated Haiti’s slaves. It’s also a voice that is heard when reading M. Bell’s memoir Soul in a Bottle and his biography of Tousssaint Louverture.

The effect of writing in so many voices is to reinforce the reader’s awareness of the depth and breadth of the source material, which in turn engenders a sense of verisimilitude. The reliability of a story is enhanced when it is told consistently by many witnesses.

Child is structured with a preface, eight chronologically ascending Parts, each bearing the title of the novel Bob Stone wrote during the era covered by that Part, and a coda. Each Part is divided into chapters. Early chapters in each Part begin with biographical narrative. Later chapters cover the time when Bob Stone was writing the novel for which the Part is titled.

In the concluding chapters of each of Part, M. Bell analyzes principal characters and events in the novel being considered and compares aspects of the characters’ personalities to similar character traits of Bob Stone and to events in Bob Stone’s life. In the preface, M. Bell writes: “He was a conflicted, sometimes tormented personality in both life and art. . . . Although Stone was never an autobiographical novelist . . .some variations of his own qualities . . .” are usually “projected onto at least one major character . . . or sometimes . . . is split between two protagonists.” Is M. Bell saying that these are instances of art mimicking life? On a superficial level one might be inclined to say yes. But Child takes its readers too deeply into the life and art of Robert Stone for the answer to be obvious.

Bob Stone’s story “Dominion” was published in the last issue of The New Yorker of the 1990s. It followed by one year the publication of his sixth novel Damascus Gate. The principal character is Michael Ahearn, whom Stone borrowed from Arctutus. Ahearn appears again as the main character in Bay of Souls, Stone’s penultimate novel published in 2003.

In “Dominion,” Ahearn is a lapsed Catholic who may be moving toward rediscovering his faith: religion is on his mind. When returning from a hunting trip, he learns that his son, Paul, had been overcome by the cold while outside searching for his dog. Paul is hospitalized and near death from freezing. When Ahearn learns that his son will survive, he turns his back on the hospital chapel.

Bay of Souls begins with a reprisal of “Dominion:” Ahearn on a hunting trip like the one in “Dominion.” Paul almost freezes to death. When Bay of Souls continues beyond the events in “Dominion,” Ahearn has an extra-marital affair similar to Robert Stone’s own long-lasting extra-marital affair. Ahearn travels with his mistress to an exotic Caribbean island as Stone did with his mistress. Ahearn’s wife discovers the affair when she finds two boarding pass stubs, which is exactly how Janice Stone discovered her husband’s affair. (Stone’s marital indiscretions had a happier ending than Ahern’s did. Ahern’s wife divorced him, taking Paul with her. Janice Stone gave Bob an ultimatum: “Her or me.” Pondering his decision, Bob asked Janice if she would still be his secretary if he chose her rival. But he quickly came to his senses, saving his marriage.)

Robert Stone was expelled from St. Ann’s because he’d advocated atheistic humanism. But in maturity he increasingly professed faith and began writing about the vicissitudes of religious belief. Thus, it is reasonable to ask: Did Stone imbue Ahearn with spiritual anguish akin to his own to learn how his character would come to terms with his lapsed faith not. If Bob Stone wrote about Ahearn to benefit therapeutically, then we have an instance of life imitating art.

On the other hand, did Stone write his own life into Ahearn’s to mask an imagination impaired by a fog of debilitating pain and intoxication? Within Child we find evidence of this sad possibility. Although Bay of Souls is a powerful and very interesting book, it was Stone’s only novel that did not receive critical acclaim. Its beginning is a copy of “Dominion,” major turning points in its plot mirror similar events in Stone’s life, and a decade would pass before Stone published his next and final novel, Death of a Black-Haired Girl.

The answer to the question of whether the work of Robert Stone belongs closer to the position staked out by Aristotle than it does to the camp established by Wilde cannot be found in Child of Light. But Child supplies sufficient relevant information coupled with astute literary analyses that enables its readers to develop educated opinions and to provide an informed springboard to wherever such an inquiry would lead.

When I finished Child, I had a feeling that I’d lost a friend I’d known well and had admired. Not wanting the story to end, not wanting to believe that Bob Stone’s life had ended, I wanted to turn back to page one and begin reading again. One day I will read this book again. But this spring, Madison Smartt Bell has published three books that I know of. In addition to authoring Child of Light, he has edited and written an introduction to and commentary for The Eye You See With: Selected Nonfiction of Robert Stone. And he has edited a Library of America compendium of three Robert Stone novels: Dog Soldiers, A Flag for Sunrise, and Outerbridge Reach.

The call of these books overpowers my desire to reread Child right away as does a call to read more novels and stories authored by Robert Stone and novels authored by Madison Smartt Bell that I haven’t yet read. M. Bell says in the preface to Child of Light that Robert Stone was one of those rare authors whose novels warrant multiple readings as fresh insights are offered each time. I trust M. Bell on this point as I would say the same of the eight or nine books that he wrote that I’ve read. I’ve reread two of his books and was rewarded each time with fresh insights and pleasure undiminished by the first reading.

If M. Bell is nearing a completion of Arctutus, then I’d have a perfect solution to the problem of what to read next.

As Robert Stone was, Madison Bell is a critically acclaimed author and a college professor. His accolades and accomplishments (eighteen volumes of fiction, two biographies, a memoir of his travels in Haiti, for example) are far too numerous to mention here. He’s been a finalist for the National Book Award and for the Pen-Faulkner award. His stories have been selected for publication in Best American Short Stories. He’s written for a long list of leading magazines, including Harpers and The New Yorker. Since 1984 he’s been a professor of English at Goucher College, where he is a co-director of the creative writing program.

Before writing this review, I purchased an e-book version of Child of Light and a hardcover first edition. Before I began writing this review, I read the e-book because e-books are searchable. I frequently referred to my hardcover copy while writing the review.