Used as an adjective, “novel” means original or striking in conception or style: strange, unusual. Or more simply, quoting Ron Carlson addressing a writing workshop I attended at Kenyon College, novel means something new. Used as a noun the word can mean: an invented prose narrative of considerable length and a certain complexity that deals imaginatively with human experience through a connected sequence of events involving a group of persons in a specific setting.

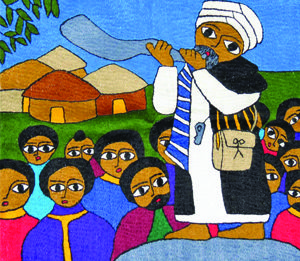

This gave me the idea to make everything in The Speed of Life new if I could. I told the story in part through a court opinion in Part V, “Merchants of Justice:” fiction posing as nonfiction. In Part II, “Andrew,” I included a Seminole folk tale: How Dog Lost His Voice.

One part of the novel is told in part from the point of view of Betty Mae, a shaman traveling in hidden reality to the outskirts of the Milky Way.

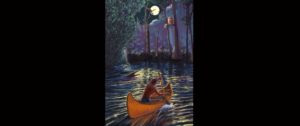

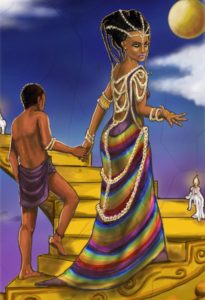

The reader also meets Georges Bohem, a brilliant successful lawyer. We see him shining in court. Then we see him at 16, trying to figure out girls. We see his losses of love, his struggles as a single father. Each chapter in which he appears illuminates him in a new way. A vital essence of his adult character is captured, I hope, in the illustration on the title page of Part III, Georges.

How do these thoughts relate to the topic of Art and Commerce? After meeting many of the gatekeepers guarding the House of Literary Fiction—editors, agents, interns—I find it easy to compare them to Dante’s guardians at the gates to the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso: the Leopard of Malice, the Lion of Violence, and the She-Wolf of incontinence. It’s unlikely these guardians want something truly new and original. That would be too risky.

This reminds me of teachers who told me over and over that “Nothing is new”. I still don’t believe them, either, James.