I give it Five Stars!

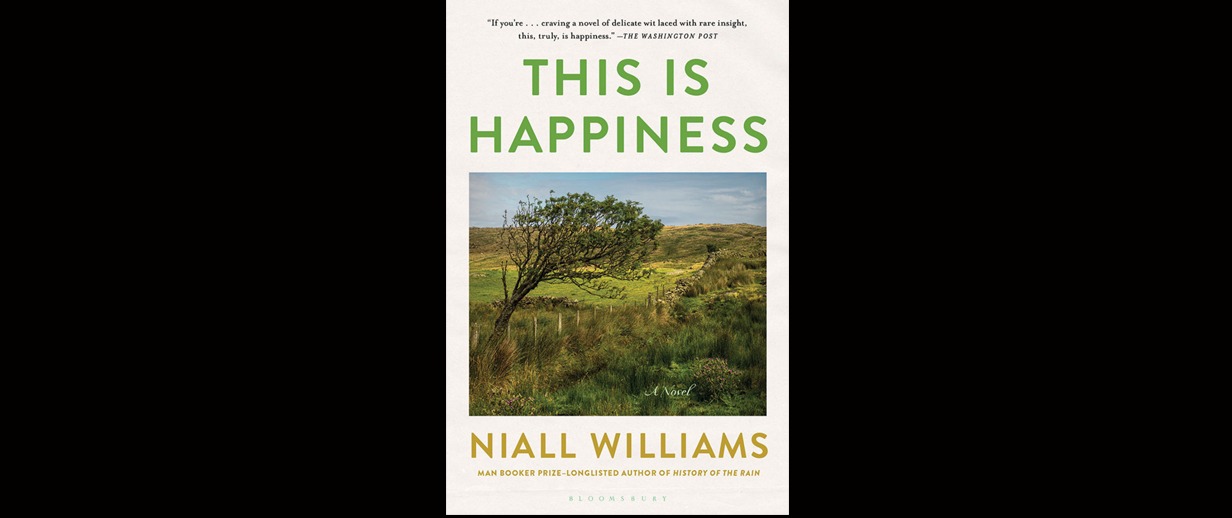

Literary fiction creates and portrays characters and settings that are vivid, poignant if not unforgettable. If does more, of course. It is told with beautiful prosody in a compelling, charming, unique voice. It is dramatic without succumbing to melodrama. It pulls at the reader’s heartstrings without slipping into sentimentality. Each of these literary virtues shape This is Happiness, the ninth novel authored by the Irish writer Niall Williams, whose previous novel, History of Rain, was longlisted in 2014 for the Mann Booker Prize.

This is Happiness is populated with several remarkable characters. The narrator is 78-year old Noe Crowe, who tells the story of a spring and summertime he spent with his grandparents in 1958 when he was 17 in a fictious village known as Faha, County Clare, Ireland. Noe was then a recent seminary-school dropout, mourning the recent death of his mother. Because the narrator reminisces about events six decades in the past, he can credibly make more meaningful observations about these memories specifically and life generally than he could have when he was seventeen. Moreover, the stories do not have to be told in the voice of a teenager but rather can (and do) transition into adult-speak before returning to the believable voice of a youth experiencing the events as they are told. The adult observations and asides contribute to the remarkable voice created and heard in this novel.

Noe comes to Faha from Dublin to live with his grandparents, Ganga and Doady, who live on a farmstead on the outskirts of Faha. In 1958, Faha, County Clare, Ireland, where the novel is set, is a (fictional) village where halfway through the 20th Century “the parish finally steps out of the 19th”. Not one character fits the stereotype of an Irish-country bumpkin. To the contrary, while Ganga and Doady are the first householders to have a telephone in the environs of Faha, they are the only ones who refuse to take the electricity when it arrives in the village toward the end of the novel: a delightful surprise that seems to have been inevitable after the fact.

Faha is made exceptionally vivid by the fact that to get around, Noe usually must walk or ride a bike. Therefor most scenes are described as Noe passes them by at an ambulatory rather than an expressway pace. The pace is so gentle that it’s (almost) as if the reader can taste the dust rising from the unpaved roads in late spring and summer dry heat. At night one can only see by the light of the moon or the flame of a candle as the villagers wait for the promised electrification.

Shortly after arriving in Faha, Noe meets Christy McMahon, who becomes his grandparents’ lodger, sharing a room with Noe. Christy has come to Faha for professional and personal reasons. Professionally he’s there as an employee of the electric company to assist with the sale of electricity to the populace and to assist with the logistics of electrification. Personally, he’s come to try and make amends to Annie Mooney, whom he left standing at the altar decades before. Of course, this brings to the reader’s mind as well a Noe’s, the great Charles Dickens character, Ms. Havisham. But Annie, who is no Ms. Havisham, having moved on to a splendid marriage to another and with no apparent psychological wounds, is distinctly uninterested in meeting Christy again, let alone conversing with him. Noe recalls:

“I was surprised that Christy was not more downtrodden by the impasse with Annie. . . . I asked him why.

“‘Noe,’ he said, and drew a theatrical breath, ‘this is happiness.’

I gave him back the sort of look you give those a few shillings short of a pound.

‘I know,’ he said. ‘Whenever I said that it used to drive my wife mad.

‘You were married?’

‘I was. She left me for a better man. God bless her,’ he said, and nodded down the valley after the memory of her. He smiled, quoting himself: ‘This is happiness.’

It was a condensed explanation, but I came to understand it to mean you could stop at, not all, but most moments of your life, stop for one heartbeat and, no matter the state of your head or heart, to say This is Happiness, because of the simple truth, you were alive to say it.

I think of that often. We can all pause right here, raise our head, take a breath and accept that This is Happiness, and the bulky blue figure of Christy cycling across the next life would be waving a big slow hand in the air at all of us coming along behind him.”

This (a moment in a lifetime) is happiness because at whatever moment in life you choose, you can pause and reflect that you are still alive. This defeats the alternative, usually, and for most of our lives. For in such a moment of reflection, taking stock, one can change course, aiming for a different destination from the one momentum had been taking you. It is therefore in this context that the reader is left to ponder Noe’s first kisses, exchanged with the inestimable, Charlene (Charlie) Troy.

“The time it takes for one face to meet another’s is in fact no time, it’s so charged as to be outside of ordinary measure . . . My kiss is the lightest touch on a surface soft and sticky. It’s a kiss of imagination and worship. . .

“Charlie’s kisses were, I suppose, in The Book of Kisses . . . in the chapter called devouring. There was biting and gnawing and teeth-banging in them, an urgent air of mouth-to-mouth combat . . .”

This is Happiness is, as I hope these brief quotes and my comments show, an exceptional novel. There are, however, passages in the reviews of This is Happiness that are critical of the novel and with which I disagree. The following was said by Elizabeth Graver in The New York Times Book Review:

“Where the book’s digressions sometimes bog down are in its more self-reflective moments: Noe the storyteller defending himself against charges (but whose?) of sentimentality and holding forth on the relationship between story and truth, the real and the imagined, and the enriching merits of the arts.”

It is these self-reflective moments that give life to the extraordinary voice that narrates This is Happiness and to the events, feelings, and insights remembered.

In The Washington Post, the critic Ron Charles wrote:

“If Faha isn’t for everybody, then neither, frankly, is Williams’s novel, delivered in the pensive voice of a man in his 70s recalling his youth. ‘This in miniature was the world,’ he writes, but that demands a kind of attention and patience that’s increasingly scarce. If you’re in a hurry, hurry along to another book.”

I don’t imagine that fans of literary fiction are in too much of a hurry not to linger over the exceptional prose or be stirred by Noe’s sixty-year-old reminiscences. Nor do I agree that the voice is pensive.

After satisfying myself that I’d rebutted such criticisms, I concluded without further hesitation that this novel deserves five stars. If you read it, you will be entertained and enriched.

that was a very thorough review, and really took a deep dive into the central philosophical revelation of the book. thanks!!

Excellent review, James!! I loved the kiss scene – like no other!!